Beyond Scrum

In too many places and for too many people, Agile means Scrum. And vice-versa.

Over the dozens of interviews I've done in the last few years, trying to understand how candidates were thinking about "agile software development", the answer, 80% of the time, describes the Scrum process. When trying to dig into these candidates' knowledge about how software should be designed and planned, and why, I hit the wall of Scrum theory, and I'm amazed at the lack of understanding of the fundamental reasons behind some of Scrum's aspects.

This might sound unimportant: this framework exists, so why not just use what's out of the box right? My take is that this blind dependence on Scrum is preventing the industry from maturing and embracing the specific nature of Software Engineering, as much as getting the right thing done right... (and not only getting something done). This one-size-fits-all framework, and the lack of understanding of its underlying mechanisms, gives an excuse for people to avoid just talking to each other (meetings and emails... I know...).

What we end up with is Software Engineers who can write code, but are clueless about the larger scheme of things, hence end up writing more code to account for this shortcoming. How does that materialize?

We're getting drowned in bugs or change requests -> write more code

Priorities are shifting -> parc code, write new code.

Customer is not happy -> rewrite all the code from scratch with a more performant framework

.... etc

Below is not yet another article against- or pro-Scrum. You can read it like this. But it doesn't matter. This is an article to outline my experiences with Scrum and to hopefully add perspective and put reality in the spotlight: help engineering people get out of Plato's cave. That cave where shadows are projected by so-called Agile consultants, and chains are certifications and titles.

Experience vs. Opinions

"You didn't implement Scrum properly!"

...is usually the ultimate response to any debate around Scrum, SAFe, or any of those certification-selling processes.

Sure, whatever... I'm pretty sure Scrum works for some teams' managers out there who implemented it the right way

So what's the rest of the article about :

My experiences and impacts I've seen (theory vs. real life)

Signals that you should stop feeling guilty about Scrum and get out of the cave

What's beyond (or behind, or under...)

Experiences

Estimating non-linear, highly-dependant, creative tasks

Theory: Story points or even hours. Estimates are just estimates. They are here to give us a "sense" of how complex things are. They can be used to measure progress or productivity - velocity - or help plan your next Sprint from actual data.

(Don't worry, nobody will say anything if that 3-point story is not done in 3 days. Right?)

Experience #1: Story points are not natural. It helps in some situations to use abstract metrics like t-shirt sizes to help prioritize high-level bets or initiatives. I've used those successfully in some situations. But engineers need precision when they evaluate tactical work that is supposed to have a precise outcome in the next 10 business days. What's the story point?

Immediately after a team starts using story points:

Infinite discussions between Kevin and Karen to get to the "perfect estimate". Debating between 3 and 5 for, like, 35 minutes, while others are sharing memes in Slack.

Gaming the estimates to make an additional story fit (or not fit) in the next sprint. Plus never-ending-multi-channel-discussions about it once the Scrum Master realizes how much people don't "get story points".

Change of estimates during the sprint, or in the next sprint. Because it was simpler. Or more complicated. Or already half done. Or worse: the assignee changed! Making your velocity a little bit more useless than it was already.

The subject surfaces in every retro: "I'm not sure we're aligned about the real meaning of a 3". Or, "Why can't we use a 1.5 if it's half a 3?"

None of this is helping the product being built, or helping your stakeholders understand it. It's noise.

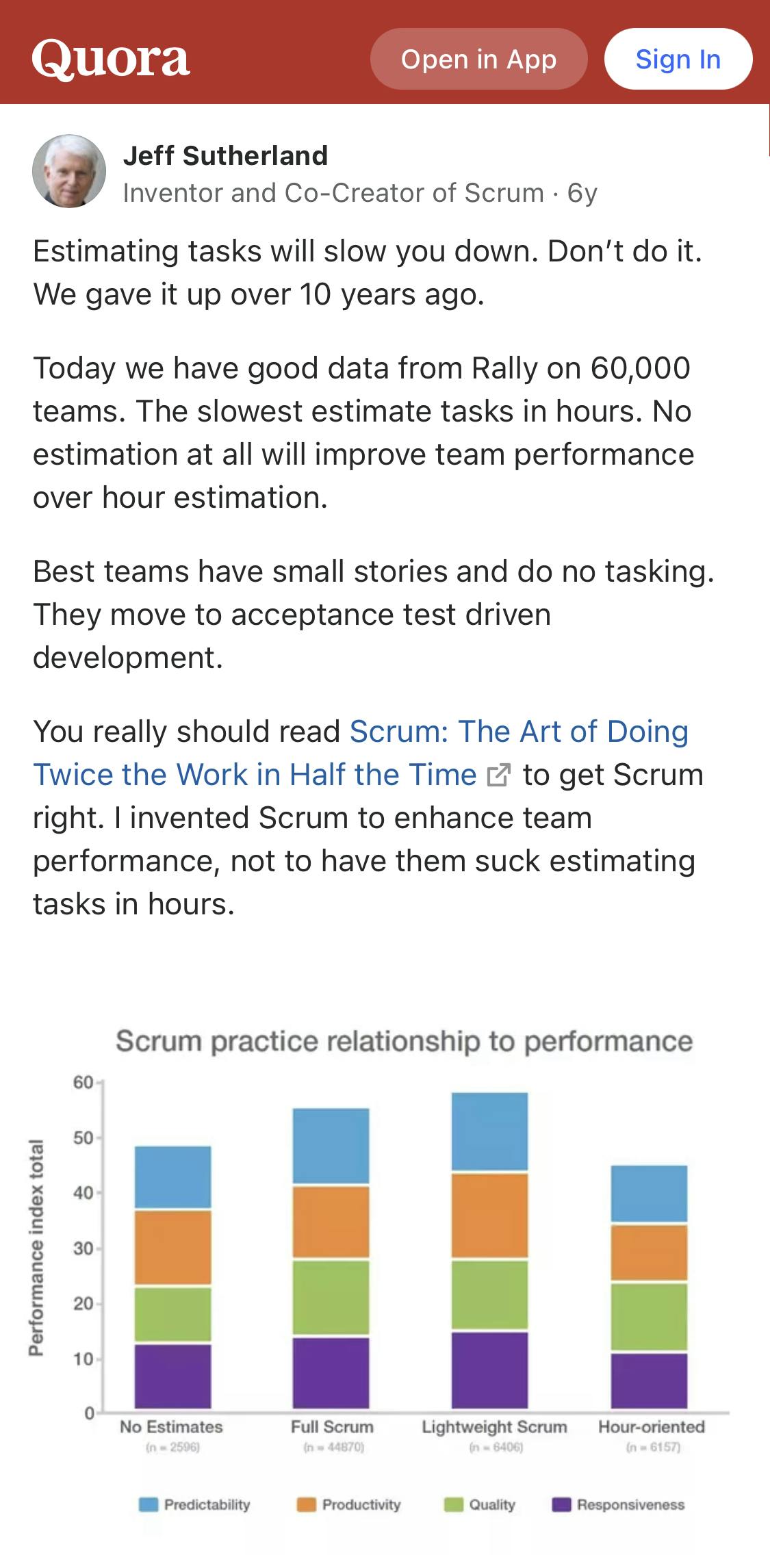

Experience #2: Teams using hours to estimate stories. This is great for tracking individuals and invoice consulting hours. But how is it useful for the team, since 3h of Kevin != 3h of Karen?

What's the use of the team velocity in hours, since the number of hours in a sprint is constant? There are only 2 debatable reasons to estimate tasks in hours:

People with a higher rank are asking you for commitment, or want to "measure productivity", and you want to keep them off your back, so you throw some metrics they can understand during the 47s of the attention span they have. These people probably wouldn't get how DORA and SPACE work anyway ;)

Your "working time" is invoiced to a customer (you're a consultant, Harry).

Additionally, biases such as the planning fallacy and optimism bias make us super bad at estimating things. Software Engineering involves a lot of uncertainty (e.g: that one breaking change in the critical 3rd party that just wrecked the CI? anyone?)

Experience #3: People who "get story points" spend hours in meetings and retros with stakeholders and teams, trying to explain story points... Just to hear the VP of Sales asking when stuff will be ready.

That time spent, trying to align everyone on the meaning of estimations and how to get the "perfect estimation" (oxymoron alert!), accounts for some of the most useless I've spent in my career. I regret it.

Estimating is essential to business and communication, that's reality, especially in large projects. But in large projects, there's more than one team and the Scrum estimation madness at the team level is useless, as it's disconnected from the reality of the business. Leave that to the Global Portfolio Manager in Chief.

But you can make up your own mind: here or here. #NoEstimates

Also, from the creator himself...

Artificial breakdowns, artificial stories, artificial sprint lengths, unaligned incentives.

Theory: As a [Persona] I can do [X] so that [Y]

Experience #1: As a Random Generic User I can do [X/2] so that I can barely achieve [Y-after-the-next-sprint-maybe]

Experience #2: As a QA Engineer, I can test [X/2] because apparently developers achieved [X] in the last sprint.

Experience #3: That one task that has been jumping from sprint to sprint since the beginning of the year, "In Progress", because it's the most important one and no one acknowledged that it cannot be done in 2 weeks. (Worse: it started as a 5, became a 1 after 3 sprints, and is now back to 8...)

We should care first about the outcome of the work we do. And not care if it can be done in 2 weeks or not. But in reality, in each retro, we end up discussing how our incentives don't align with the process, rinse and repeat...

...Until people end up saying "We're using a custom form of Scrum... Not really by the books"

Experience #4: "Let's do 3 weeks-sprints, we'll have more time for QA stuff and deployment". (Also 1 week more should help that guy finish the task he has had in all the sprints since the beginning of the year.)

Sprint length, 2 weeks, 1 week, 3 weeks, doesn't matter. This is artificial. What matters is making baby steps, and avoiding "Work in Progress". What matters is regularly, consistently, telling your stakeholders what's up, what's down, what's deployed, what's crap, and what's missing.

Some tasks are unbreakable without also breaking their value. Some other tasks are unassignable to a good persona. That's reality. Having a good-enough-CI is not benefitting a persona, it's benefitting the entire company, team, and all the customers by transitivity. Failing to understand that is failing to understand how modern software works.

What happens usually is to "comply" with Scrum's artificial sprint length and artificial "guidelines", teams are breaking down things artificially instead of focusing on why these things are important in the first place. Because the incentive is about velocity and looking sharp enough at ceremonies, not about the value itself.

Real-life testimony as I write this: Since we adopted Scrum, I have the impression we only work on low-hanging fruits. Not on important but complex, hairy background problems anymore.

Experience #5: Teams rushing to push their last PRs last day of the Sprint, while the QA is in a panic because they're still creating bugs from the last sprint and don't have time to test the work of this one, while the demo meeting has started, and one of the devs presents the "achievements" on his laptop, "soon-to-be-pushed-branch", with disabled unit tests... (because they're all obviously breaking-red).

Individuals vs teams

Theory: Scrum is a team sport. The Sprint is for the team to achieve. The team is full-stack and can do it all. We succeed together or fail together.

Experience #1: Tickets being customized for the assignee. Every. Sprint. People are uncomfortable having no ticket assigned to them at the beginning of the sprint. So better to look busy than take a couple of days, free up brain cycles and look for real impact.

The benefit of having "time to think" or "get bored" is well known in highly creative, knowledge work. On the other side of the spectrum, busyness tends to slow down people around (undercover interruptions of lower priorities). These facts are rarely taken into account when planning a sprint. How could they?

People still need tickets to "block time" to be able to think. They call them "spikes" and spend time inventing titles with keywords like "PoC" or "draft" in them. Because if it's not in a ticket, it doesn't exist. And we need proof that those brains we hired are actually "braining" each second we pay them for. Also, we need to keep that velocity at make-believe standards.

Experience #2: Estimations made only by the person who created the ticket. Not by the team. Anyway, tickets are personally assigned, so why bother the team for estimations right? The only person who can do that is probably also the only person who can decide between 3 and 5. Another thing Scrum makes us feel bad about.

Experience #3: "Full-stack" doesn't mean anything. Even if I believe in cross-discipline teams (one definition of "full-stack"), the reality of the tech landscape, hiring, firing, human beings being what they are, budgets, and day-to-day life, makes it impossible to have a truly full-stack team. You'll always miss expertise somewhere. Or have additional expertise you don't need today.

The mythical "Innovation sprints" and "Quality sprints"

If you don't have time for it day to day, planning it once a quarter won't make it happen. By it, I'm talking about Quality, Innovation, Non-Functional Requirements, or Documentation.

Like some wise folk said once (on LinkedIn probably): Doing "Quality sprints", or "Tech Debt sprints", is like eating salad every Monday evening while eating fast food the rest of the week. That's not making you healthier.

Experience #1: Scrum teams pack their sprints with "coding" activities because they don't know how to estimate or make room for other activities not related to coding. Coding activities yield tangible results for stakeholders. Like measuring developer productivity with lines of code written. Yikes.

Because they get pressure from stakeholders (and from Scrum itself) to deliver value each sprint. Because Scrum measures success in velocity and sprint goals only. Because value is measured in buttons we can press. All this doesn't play well with "Innovation" or "Research". This doesn't play well with modelling, designing, or thinking before doing.

I know, you can plan "Spikes" again. However, the incentive structure goes against those activities. What do you demo if you spent your whole sprint trying to master a technology that will make you 5x more productive 3 months down the line? How do you keep the Head of Something interested in the demo when showing a command line interface that displays a net performance gain of 26% for something he didn't even know existed?

Experience #2: The "innovation task" is the first one to be pushed out when inevitably the other tasks take more space in the sprint. Again, we're just bad at planning. Being bad at planning with Scrum, means no initiative not fitting the 2-week eyesight will get a significant priority boost. You'll end up navigating the year sprint by sprint. Carpe Diem.

No! "PI planning" and SAFe are not solving this issue. It's just scaling the issue so we can feel bad about it only 4 times a year instead of 20 and with more colleagues.

Commitments

Your stakeholders don't get Scrum. No matter how much you explain. They would get it maybe if they experienced it. But they didn't. They barely accept it as a weird habit as long as it doesn't get in their way. They are still stuck with the mental model of software engineering being compared to how houses or cars are designed and built anyway.

Your stakeholders care about when they will get the value in their hands, and how much that value is going to benefit them. They don't care how you achieve that.

Experience #1: Companies have yearly financial plans. Customers want dates because they need to plan, according to their yearly financial plans. They don't care about burn-downs and are going to ask "When is it ready?" at every possible opportunity. Teams who "get that" do a better job at focusing on scope and keeping their stakeholders in the loop as often as possible. Teams who don't get that hide behind their story breakdowns, story points, sprint plannings, and burn-downs because they have nothing else to show and they already spent all their "planning time" deciding between 3 and 5.

Experience #2: Things will come up in the middle of the sprint every now and then. Guaranteed. Unless you're in the most stable, innovation-free, dull business in the world with no competitors and no future. Breaking a sprint is seen as a failure because Scrum tells you that the sprint should be atomic: it's here to "protect the team" from interruptions.

But why would it be a failure, if you were able to solve a more important customer problem that was unforeseen? You're not "building a perfect Scrum operation". You're supposed to deliver value to customers.

"Protecting the team" is also a dangerous endeavour that usually ends up in "Isolating the team" from the real world. What should be protected is the focus, and the ability to deliver what matters despite the noise. It should be protected from Work-Forever-In-Progress, Feature-Creep, and Busyness-Tasks. That's probably what was originally behind the idea of the Sprint, and most likely one of the most misused features of the framework.

In theory territory: the exceptionally perfect context problem

In theory, Scrum has a lot of very nice features. It forces you to break down work, focus on a few controllable things at a time, measure the team's way of working, avoid BDUF, encourage regular feedback and interactions, etc.

But in theory, engineering teams are also organized by the books and organizations are mature and have a stable business. And I've yet to find an ideal team and organization out there.

Fullstack teams in theory. In practice, there's always that skill missing. Or that budget missing to hire that specific role. Or that dude who would rather sell his parents rather than touch Javascript.

Business teams know what they want in theory. Company goals are clear in theory. In reality, if what's upstream is messy, what's downstream is going to be the same, squared. Say bye-bye to your unbreakable sprint.

In theory, everyone in the org understands how software works, is built, is maintained, and why it's very different from other engineering practices. In practice, even software engineers have trouble explaining that clearly to their stakeholders. We're still using bad analogies to explain software because people can't understand how (re)naming could be harder than bootstrapping a whole new service. People have a hard time comprehending scales (peta? giga? nano?) and locating where "virtual" is on the map of the universe.

In theory, you have 1 team using Scrum. In reality, you have multiple teams working more or less together at different times of the year. Each has a different mix of real problems. Again, if you're thinking of SAFe or "Scrum of Scrum" now, you're missing the point: this is scaling the issues, not the solution.

Should you drop Scrum?

Not necessarily. One could argue that the matrix framework is somehow comforting. And maybe that decision is not even yours (which would tell a lot about your company).

Here are the signals that would tell you you need to stop lying to yourself at least:

It takes you more time to estimate than to write and execute stories.

Burndowns look like the Niagara Falls or the Himalaya mountains. Consistently.

People are arguing about Fibonacci numbers more than about the relevance of the content of the ticket. They are also using the word "ticket" for everything their day is composed of.

Non-functional requirements always get pushed out. Technical debt is negatively viewed as an "Engineer's problem" rather than promoted as a "tool" enabling delivery and agility.

You can't plan outside of a "planning" meeting. You can't collaboratively design/architect things outside of a "refinement" meeting, and you can't "release" outside of a sprint schedule (RIP DevOps). These 3 things (plan, design, release) are not even yours to do most likely.

People feel stressed about their sprint goals, rather than focusing on their stakeholders' problems and stressing about their services being well monitored.

Subject surfacing in retros are often the same and feel like nitpicking constantly over details that couldn't be further away from your customer's concerns... Or are completely out of the control of the team.

Your team has usually no clue how their stories relate to the higher scheme of things, or what awaits them beyond their next 2 weeks.

Your sprints are regularly, carefully, nonchalantly wrecked and redirected. Especially the "Innovation sprint"...

Words like "Tickets", "Daily", "Commitment", "Velocity", "Estimation", and "Sprint", dominate or even drive ALL discussions. Even those where you should be talking about why you're even here in the first place, or why your customer is thinking about going to the competitor.

Dropping Scrum is not the right question. The right question is: Do you understand why you're using Scrum if you do?

How to unscrum yourself

In theory, Scrum has nice features. And those features, when you understand them, show you what you should focus on in your day-to-day. Once you get the why, you can stop feeling guilty about not using "Scrum by the books".

Scrum feature | What's behind | What's beyond |

Short sprints | Respond to change, Don't over-plan, and accept that priorities will shift. | How short doesn't matter really. Just make sure it works for your team. The regular bi-weekly basis is fine, but don't feel guilty about it. Try the radical constraint idea: make it a week, or even a day! |

Sprints should not be broken | When there's shared commitment and you removed risk and uncertainties, focus on just this iteration, to avoid Work-in-Progress | Seek commitments from the team, but also from stakeholders! Surface the risk, and start coding only the risk-free parts. Protect the focus. Given priorities are right, focus on #1. |

Demos | Give regular updates about the progress. | Why not every week? Why not every time you merge to main? Why not every time you feel proud of yourself? Just record it and send it to all. |

Plan each sprint | Planning is more important than the plan itself. Do it often, if you get it wrong once in a while, it won't matter anymore. | Start working on what is known now. Keep the uncertainty for another discussion. Have an honest discussion about ETAs to prod, dependencies, breakdown of work, and risk. Focus on the priority. |

Release each sprint | Release often. Get your work in production. | Honestly, this one is outdated. You should be releasing more than twice a month. But the principle remains. |

Refinements and grooming | Clarify the unclear. Often, not just once. Question assumptions, make hypotheses and validate them quickly. Discuss that hairy, complex problem to tame it. | Don't do it only every 2 weeks. You should constantly be doing it, even when you already started work. Halfway through that well-specified ticket and finding a gap? Raise it. Challenge, question, discuss, agree, commit. Because it's already well specified doesn't mean it's still the right thing to do. |

Story points | Have an honest, safe conversation about complexity with stakeholders. Measure velocity. Data-driven planning. | Stop. Just stop. You're wasting your time. Try measuring your cycle time instead. That’s useful data for planning. If you want to measure productivity, there are plenty of better frameworks out there. |

Scrum Master | Non-coding work is actually work that justifies "paying someone".. who would have known? | The combination of a good Product-minded person (usually PO or PM) and a good Engineering Manager that has a servant leadership mindset should solve all your problems, and empower your team and individuals instead of treating them like hamsters in a wheel. You don't need a certification to talk to people. |

Break down stories to fit a sprint | Baby steps are the only way to tame complexity and over-engineering. | When you think it's broken down enough, do it once more. And repeat. |

Retrospectives | Make room and create safe moments to talk with your teams about how you work, not only what you are working on. Take time to reflect, and give feedback. | Just reserve time in calendars. The cadence doesn't matter. What matters is that people are happy to come and have valuable things to say. Make it safe. |

If you experience Scrum-pain symptoms, go back to the basics. Here's one simple thought process that should work every time:

What's the #1 priority for the team? You're part of a company. Think about customers and revenue. How can you help? What's the one thing that has the most impact now? Don't think about sprints. Think in terms of value. Use radical enabling constraints to remove the noise. By definition, you can't have 2 priority #1...

If you don't know what's #1, it's time to find out! Talk to people.

Refine that one thing with the team. Refine until you're comfortable starting on it. Don't limit yourself to the "1 hour meeting". Don't pressure yourself with a sprint start. Just break down complexity, and ask questions, until you have something small and easy to start with.

Work on that first iteration only and ship it! Test it, validate it, deploy it in prod, and ask everyone to look at it.

If not everyone can work on that prio #1, don't over-plan. You don't have to fill everyone's week with tasks. The only way to account for planning errors is to keep room for them in the plan. Leave room for people to "think" and "help" on topics you didn't foresee. Unpopular opinion: I'd rather have an engineer read a book for the next 10 days than have him bother people working on prio #1, because he's stuck on prio #12...

On processes and frameworks

Recently I stumbled upon this nice piece that essentially says that most “frameworks” are teaching frameworks. Starting points. That we should quickly evolve from them.

It's like the scaffolds when you build a house. Or the small training wheels on your first bike. They get you started and help you master the breaks and pedals before you have to care for balance.

You want to get rid of the scaffolds before living in the house though, and keeping the training wheels too long is not going to help you master the bike.

Well to be fair, you don't have to. It's just not fun living in a house with scaffolds around. And keeping the training wheels will prevent you from learning about balance, and going faster (again, not fun).

That's maybe the thing to remember here. Scrum is just one framework. If you're serious about Software Engineering, maybe you need to build your own already.